Students Work to Close the Loop by Recycling Plastics Used in Labs

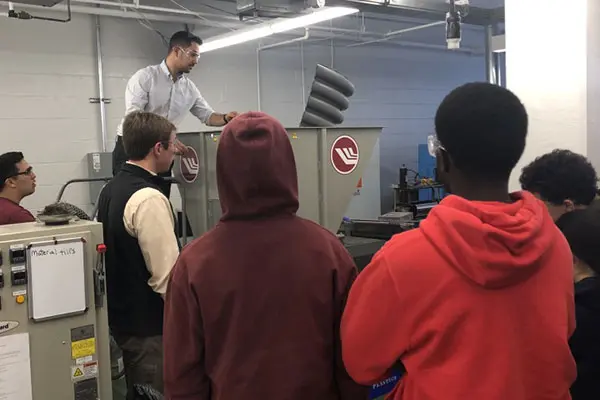

Asst. Prof. Davide Masato feeds large plastic waste into a Cumberland shredder as Assoc. Prof. Stephen Johnston looks on, at a recycling challenge for students from the Boys & Girls Club of Greater Lowell. The event was co-hosted by the plastics recycling capstone students and the student chapter of the Society of Plastics Engineers.

03/21/2020

By Katharine Webster

Plastics engineering major Shnaidie Macajoux and her family emigrated from Haiti, which has huge piles of plastic trash everywhere, and almost no recycling infrastructure. So, when she saw an opportunity to do her senior capstone project on plastics recycling with Assoc. Prof. Stephen Johnston ’05, ’07, she jumped at the chance.

“Haiti has a big plastics problem, and I’m really hoping that I can help with the problem,” she says.

Her close friend, Hikma Abajorga, signed up too. Abajorga hails from Ethiopia, which has a similar plastic trash problem. Both say that they knew nothing about recycling until they came to UMass Lowell to study — but now they are converts.

“Prof. Johnston had a lot to do with why we chose this capstone. He’s a great professor,” Abajorga says. “And recycling is a big issue right now. I’m also writing a blog about recycling for Prof. Margaret Sobkowicz-Kline. I’m in her research group as an assistant. She’s amazing.”

Macajoux and Abajorga joined two other seniors, Erin Wooldridge and Kevin Bowen, in the two-semester capstone project: closing the loop by working to recycle as much as possible of the plastic waste generated by teaching and research in the department. In practical terms, that means grinding up the plastic waste from the injection-molding, blow-molding and other teaching labs into pellets that can be reheated and reused in the same machines, while finding external partners who can recycle plastics that cannot be reused on campus.

The seniors’ work builds on the capstone projects of other students who were advised over the past two years by Sobkowicz-Kline, whose research focuses on renewable and biodegradable polymers and plastics recycling. She and Johnston, who teaches courses in injection molding and does research on industrial processes, had started talking several years ago about how they could lead by example and recycle the plastic waste that the department generates.

“We’ve all had students come to us and say, ‘I want to be part of addressing plastic pollution in the environment,’” Sobkowicz-Kline says. “It made sense to use our own department as a living lab to create solutions for plastic waste. We thought it would be a good example for industry, a good example for students, and just doing our part.”

Over the first two years, the capstone students collected data on how much and what kinds of plastic are used in the labs, including for injection molding (for solid objects), blow molding (for hollow objects, such as water bottles) and blown film (for sheeting and packaging). The department uses about 2,000 pounds a semester for classes, and probably another 1,000 pounds of virgin plastic for research, Sobkowicz-Kline says.

The injection molding lab already has a full Industry 4.0 Wittmann Battenfeld machine, including robot and grinder, thanks to mechanical engineering alumnus David Preusse ’85, president of Wittmann Battenfeld’s U.S. division.

Last year, for his Honors College capstone, then-student Dan Barbin ‘19 wrote a successful proposal for a university Sustainability Engagement & Enrichment Development (S.E.E.D.) grant. The $3,700 grant paid for a portable, flexible conveyance system that can be used in multiple labs to collect plastic waste.

This year, as Sobkowicz-Kline went on sabbatical and Johnston took over the capstone, the students moved into the implementation phase: setting up and testing the grinders, figuring out a collection system and establishing protocols and procedures so that recycling becomes an integral part of all lab operations.

Wooldridge focused on the Wittmann Battenfeld machine. Bowen assembled a portable grinder, using equipment the department already had, while Abajorga and Macajoux worked on protocols for the other machines. They also began training students, teaching assistants and other faculty — until their work was cut short by the closure of the campus over concerns about the spread of COVID-19.

“The students’ goal for the year was to change recycling culture within the department,” Johnston says. “Now, they’ll be concentrating on rewriting the students’ lab manuals, and it will be up to Meg [Sobkowicz-Kline] and me to get the rest of the faculty and teaching assistants on board next year.”

Abajorga and Macajoux also worked with Johnston on getting an outside partner to take any plastics that cannot be reused on campus. Johnston says cementing a partnership with Casella Waste Systems for most of the plastics was key. He and Sobkowicz-Kline hope to find a similar partner for the blown-film waste, which currently cannot be recycled.

“Casella has built a custom program for the university,” Johnston says. While transporting and recycling the relatively small amounts of plastic the university generates is not cost-effective, Casella understands the importance of training plastics engineering students in how to deal with scrap, he says.

Providing training is also a key motivator for the students in the capstone, who all expressed excitement that they had created a program that will benefit the environment and future plastics engineering students, as well as the industries in which they will eventually work.

“Wherever I go, I want to make sure that we’re recycling in the best way possible,” says Bowen, who, like Abajorga and Macajoux, plans to spend a fifth year at UMass Lowell to earn a master’s degree before working in industry. “Having the independence to come up with ideas and do things on our own with the guidance of Prof. Johnston, and then implementing something we created that will be used by other students in the future — that’s the coolest thing.”