In New Book, Bridget Marshall Says the Industrial Revolution Helped Shape Gothic Genre

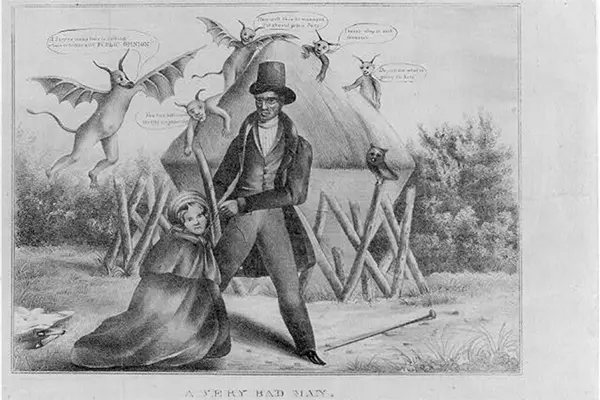

Image by Henry Robinson, Library of Congress

Image by Henry Robinson, Library of Congress 10/14/2021

By Katharine Webster

Growing up in Pennsylvania as the daughter of a casket salesman, Assoc. Prof. Bridget Marshall became more familiar with death than most children.

As a teenager, she loved Stephen King novels. Then in college, she took a course on early Gothic novels. It cemented her fascination with stories of heroines trapped in creepy homes and troubled by ancestral curses.

She ultimately became an expert in the genre, earning a Ph.D. in English and American Literature at UMass Amherst with a focus on Gothic literature.

A year after graduating, she was hired by the English Department at UMass Lowell. Here, she shares her enthusiasm in popular courses including The Horror Story, The Gothic Tradition in Literature and a new honors seminar, Factory Gothic: Horror and Industrialization. (She also got to introduce Stephen King when he came to campus to speak in 2012.)

“There’s a general obsession with the Gothic because we don’t talk about the ‘bad stuff’ in polite company. The Gothic lets us delve into the darkness from the safety of our reading nook,” says Marshall, who has won several teaching awards here.

Marshall has written extensively on Gothic literature, including the solo book “The Transatlantic Gothic Novel and the Law, 1790 – 1860,” and “Transnational Gothic: Literary and Social Exchanges in the Long Nineteenth Century,” which she co-edited.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster In it, she becomes the first scholar to argue that the Industrial Revolution contributed to the development of the Gothic genre by “recasting the ‘maiden-in-peril in a castle’ plot as the ‘factory-girl-in-peril in a mill.’”

Gothic novels originated in England in the late 1700s, and many scholars have argued that the genre was fueled by “explosive” historical events, including the American, French and Haitian revolutions. Marshall makes the case that the Industrial Revolution, although slower, was equally disruptive and contributed to the later development of Gothic literature on both sides of the Atlantic.

As single girls and young women left their family farms to work in the textile mills of Lowell and other New England cities in the early 1800s, a parallel industry grew up alongside the factories: sensational stories about the murders of “mill girls,” she says.

Newspapers and printing businesses fed a bottomless public appetite for articles, books, plays and broadsheets about young women under siege by dangerous men: mill owners, overseers, ministers, married men and doctors who drew them into intimate relationships, and in several real-life cases killed them to cover up pregnancies or botched abortions, Marshall says.

Marshall demonstrates how the authors of popular “factory fiction” and true crime books of the period used many of the same lurid literary devices, plot elements and images as the earliest Gothic novels from England, such as “The Castle of Otranto” (1764) and “The Mysteries of Udolpho” (1794), including innocent heroines, depraved villains, gloomy settings, demonic imagery and portents of doom.

And just as those earlier books helped people deal with the fears inspired by social and political revolutions, “factory Gothic” (Marshall’s Twitter handle) helped later generations cope with the fears and disruption of technological change.

“It’s a reminder that scary things aren’t just supernatural monsters and the deep, dark past,” she says. “The Industrial Revolution also has its deep, dark parts.”

Image by British Library

Image by British Library One example that Marshall cites is the 1832 death of pregnant “mill girl” Sarah Cornell. Although first believed to be a suicide, further investigation revealed she had been murdered. Her death and the murder trial of the Rev. Ephraim Avery, a married Methodist minister, spawned a mini-industry of books, broadsides, trial transcripts and plays, she says.

While Gothic novels are often viewed as essentially conservative, harking back with nostalgia to simpler times, some authors used their melodramatic plots and descriptions to expose social ills, Marshall says.

Those works engaged the sympathies of readers who otherwise might not have cared about the plight of factory workers, enslaved people, orphaned children and debtors, she says, and they may have helped stimulate popular support for better wages and working conditions in factories, the abolition of slavery and reforms to orphanages and workhouses.

Gothic literature continues to develop and flourish, while the 19th century “mill girls” remain a perennial topic for popular novels because, Marshall says, many of the themes of “violence, destruction and dislocation” feel so contemporary.

“Factory girls were often hopeless victims, not just of men, but of systems of men,” Marshall says. “Their stories were ‘ripped from the headlines’ and then retold and reframed in very Gothic ways.”