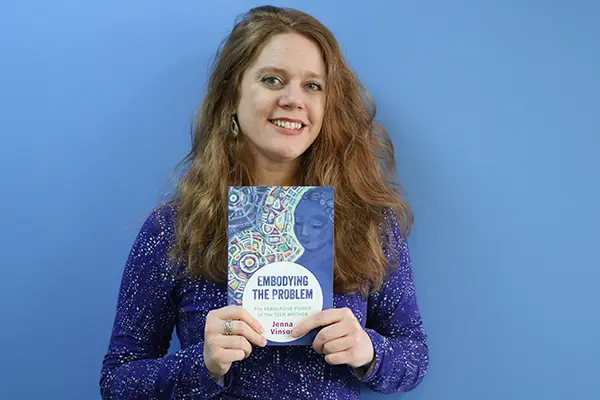

Jenna Vinson’s Book Counters Doom-and-Gloom Narrative

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

03/15/2018

By Katharine Webster

In her book “Embodying the Problem: The Persuasive Power of the Teen Mother,” Asst. Prof. Jenna Vinson examines how teenage mothers are stigmatized in teen pregnancy prevention campaigns, political discussions and the media – and how young moms are pushing back.

Vinson, an assistant professor of English, traces the rise of the narrative that teen motherhood is a major social problem and examines research that contradicts it.

Then she looks at how young moms are resisting that narrative in their everyday social encounters and in the media, often by speaking out against the actual social problems – poverty, racism, inadequate schools and health care, sexual abuse and sexism – that confront mothers of all ages and their children.

Vinson, an associate of the Center for Women and Work, teaches classes including Visual Rhetoric, Theories of Rhetoric and Composition, Introduction to Professional Writing and Rhetorics of Movements: Writing for Social Change.

She sat down with us recently to talk about “Embodying the Problem.”

Q: How did you become interested in this topic?

A: I was a young mother myself. With the support of family, friends, financial aid and state-funded health care, I finished high school, became the first in my family to go to college and went on to earn my Ph.D.

But from the time I first became pregnant and decided to keep my child, I began experiencing all the contradictions and stereotypes people hold about young mothers – that we get pregnant because we’re promiscuous or “trendy,” that we’re too immature and irresponsible to be good moms, that we have ruined our own lives and that we’ve also doomed our children.

When I was in college, I researched and wrote an essay to try and make sense of the contradictions, and I read it aloud before an audience. The response was generally positive, and that helped me realize the power of personal narratives to change people’s minds.

At the same time, I began to understand that other young moms had very different experiences, especially those living in abject poverty, those rejected by their families and those struggling with abuse or rape. In the case of young women of color and immigrants, media portrayals and anti-teen-pregnancy campaigns also draw on and reinforce racist and anti-immigrant stereotypes that they have too many children and have them too young.

The dominant narrative treats us as if we’re all the same, but we’re all so different – and so are our circumstances.

Q: You’re an English professor. How does that affect your approach?

A: I’m a feminist rhetorician, so I analyze the visual and verbal rhetoric of articles, discourses and images.

I think language has real consequences. In this case, the dominant narrative creates a doom-and-gloom context for young women who are pregnant and parenting. When people tell you your life is over, you might want to hide your pregnancy or motherhood to avoid feeling the shame or stigma. You may also be asked to leave your school, your home or your friend group. Even if the consequences aren’t so dire, you might not see that you can still do great things and parent your child.

As a feminist, I also find really problematic the idea that we should prevent an entire group of people from reproducing. It’s too reminiscent of the history of eugenics in this country.

Q: Reproductive rights are a feminist cause, and yet it seems that feminists were split on the question of teen motherhood – for example, in campaigns against teen pregnancy by groups including Planned Parenthood. Is that still true?

A: I think there is a tension, and much of that has to do with race. In the 1970s, at the very same time that white women in the feminist movement were struggling to access birth control, abortion and sterilization so they could choose not to have children, low-income women of color were experiencing the exact opposite: Their choice to have children was being taken away. They’d go to the hospital to give birth and they’d be involuntarily sterilized or – in the duress of labor – they’d be asked to sign a permission form for long-term birth control or sterilization.

Since then, more women have joined the movement for reproductive justice, which is not just about women’s access to birth control, but about pushing for changes in social structures so as to better support women who become mothers.

Q: The biggest question, of course, is “Where are the men in this picture?”

A: First of all, we don’t even count the pregnancies that teenage men father as “teen pregnancies” if the mother has passed the 20-year-old mark – so pregnancy really is seen as just being about the women.

Then, young men are seen in the dominant narrative as absentee: They’re just going to go away. And when young men are included in campaigns against teen pregnancy, the warnings are all about how it will destroy their individual futures: They won’t be able to achieve their true potential because they’ll have to get a job right away. Whereas young women are seen as creating and embodying a larger social problem.

We should always think about pregnancy and parenthood as an equitable burden and labor. We’re still struggling with that as a culture, regardless of the age of the parents.

Q: You strike a note of hope in the second half of your book when you look at counter-narratives and social media campaigns by pregnant and mothering young women.

A: The dominant narrative treats young pregnant and parenting women as “problems” for professionals and experts to “solve.” Embodying a problem is awful: It’s dehumanizing and pathologizing. But it’s also attention that you’re getting from the public, and many young women are taking advantage of this attention to change people’s minds, in books like “You Look Too Young to be a Mom,” social media campaigns such as #NoTeenShame and on the op-ed pages of newspapers.

I’m cautiously optimistic that their efforts are changing the narrative.