11/28/2014

Boston Globe

By Bella English

At Boston College High School, Nick Lavery was a strong safety on the football team, and at University of Massachusetts Lowell, he was an outside linebacker. When he enters a cafe in Braintree on a recent morning, he fills the doorway. When he orders breakfast, it’s eight eggs, hash browns, and toast.

At 6 feet 5 inches tall, Lavery weighs 220 pounds. “My leg was about 50 pounds, so I’m about 50 pounds lighter than I would be,” he notes.

That would be his right leg, which was amputated below the knee last year after an Afghan police officer opened fire on Lavery’s Green Beret team.

Lavery, a 32-year-old staff sergeant stationed at Fort Bragg, N.C., was here to visit family in Franklin and to accept the James E. Cotter Courage Award from BC High, named for its former football coach and athletic director.

It’s a great honor for a BC High kid, but Lavery has a few other medals to his name: three Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and a Bronze Star with Valor, for heroism in combat. His story is one of courage and selflessness, and offers a humbling lesson during a holiday season that is often more about getting than about giving.

Over breakfast, he speaks of his service in the Army Special Forces, which he joined after graduating from college in 2007. Sitting next to him was Mary Rizzo, whose son Jonathan was Lavery’s best childhood friend. Lavery, who grew up in Kingston, spent a lot of time at the Rizzo home, and went with Jonathan to BC High in Dorchester.

“He’s my fourth son,” is the way Mary Rizzo puts it.

“Ma” is what he calls her.

In 2001, Jonathan, a 19-year-old student at George Washington University, was carjacked and killed by Gary Sampson — who has admitted to three slayings and is facing the death penalty — after he stopped to help what seemed to be a stranded motorist.

After enveloping the petite Rizzo in his enormous embrace, Lavery settles in to tell his story. The affection between them is evident, and she looks both pained and proud as he talks.

His first deployment to Afghanistan was in 2011. In September 2012, his team was sent to Wardak province, a hotbed of fighting. The next month, his shoulder took shrapnel from a rocket-propelled grenade.

“It blew a lemon-sized hole out of my right shoulder,” he says. He refused to be evacuated for medical care, instead plugging the wound with some gauze. Finally, he was sent to Bagram Air Base to be patched up.

A month later, a truck in his unit was hit by a roadside bomb. Lavery, two trucks behind, ran to the site. “There were three enemies firing at the vehicle,” he recalls. “I neutralized two of them. The third one took off running.”

Lavery took off after him, and was hit by a bullet in the face: “I went down, but I popped back up.” The truck, on its side in a ditch, was on fire, and Lavery was certain he’d find dead bodies.

“I was amazed when I found Captain Nieman in the rubble, awake,” he says of his commanding officer. The others had been blown out of the truck but would also survive. Both of Nieman’s legs were mangled, he had a severed artery in one arm, and the truck’s ammunition was starting to fire off because of the heat.

“And we’re still getting shot at,” says Lavery. “I was pretty sure we weren’t going to make it out.”

If Lavery is a big guy, Captain Seth Nieman is bigger: An offensive lineman at West Point, he stands 6 feet 6 and 300 pounds — 370 in all his equipment. The team liked to joke that Nieman and Lavery could never ride in the same vehicle because no one else in the group could move either of them if they were wounded.

Nieman, who lost the lower half of his right leg in the explosion, told his local newspaper in North Dakota about Lavery last year: “When my vehicle was on its side, on fire, he was the only one big enough and strong enough to pull me out. He got shot, too. He got up five minutes later — that was his second Purple Heart — and got me out of there.”

In March 2013, Lavery, too, would lose part of his right leg; his team was training local forces when an Afghan police officer opened fire with a machine gun. Lavery says he hit the ground, but a young soldier next to him froze. That’s when Lavery put himself between the teen and the gunfire, tackling the kid and dragging him behind a truck.

And that’s when he was hit, several times, in the leg. He knew his femoral artery had been severed and he’d soon bleed out, so he grabbed a tourniquet from his kit. Some of his team, including the captain who had taken Nieman’s place, were killed. It was an hour before a helicopter could land and evacuate the others.

At the Army base, Lavery’s body started to shut down. Turns out they had given him six units of the wrong blood type, despite the fact that soldiers all wear their blood type on their boots, their dog tags, and stickers attached to their uniforms.

At Bagram, they gave him a full blood transfusion and put him on dialysis. He had 20 surgeries there, and after he was stabilized, he was sent to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center near Washington, D.C., where he had several more. After two months, he was discharged and began rehabilitation with a prosthesis.

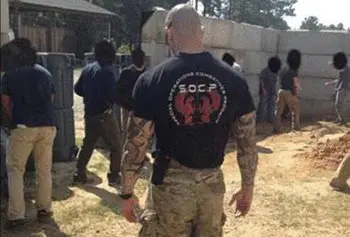

When offered medical retirement, Lavery said no. He is now a tactical combat instructor at Fort Bragg, and is working with training coaches to reach his goal of returning to combat.

“I would be on the next plane out,” he says. “Someone has to do the job, and I take enormous pride in it.”

Lavery knows the war is controversial. “I don’t think it’s a situation we can completely abandon,” he says. “But I do think we should get rid of conventional forces and leave smaller, specialized units for intelligence collection and surgical strikes. I think there’s a big upside financially and for the American people to know we’re ‘at peace.’ But we can’t turn our backs on the part of the world that still poses a dangerous threat to us.”

Mary Rizzo has left the cafe. She had visited Lavery at Walter Reed and seen his injuries up close, and she still worries about him. She’ll see him that night at the awards ceremony.