In Saving Lowell, Late Senator Saw Value in Education

02/12/2016

By David Perry

"There were three priorities in our house growing up,” says Thaleia Schlesinger, the late Paul Tsongas’ twin sister. “The family business, the Red Sox and education. And not in that order.”

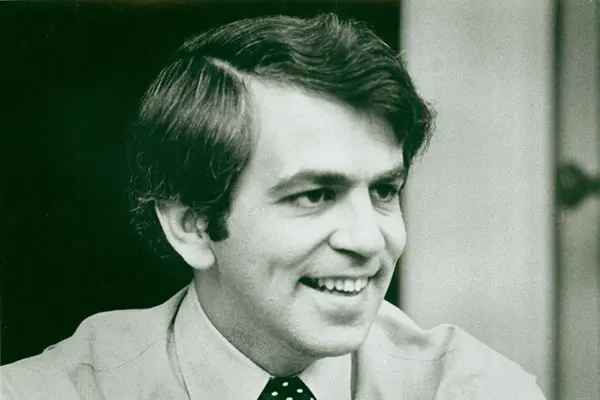

For Paul Tsongas – U.S. senator, congressman, presidential candidate, local pol and architect of Lowell’s resurgence — education was a thread that ran through the many facets of his life. And much of the story of Tsongas’s life – the Lowell native would have turned 75 this Valentine’s Day – is entwined with that of the university, from campus namesakes (the Tsongas Center, the Tsongas Industrial History Center) to a scholarship in his name, to the treasure trove of his papers housed at the UMass Lowell Center for Lowell History.

In the Tsongas household, says Schlesinger, “education was part of the ether. … Paul saw that UMass Lowell was a natural extension of how you give people opportunity.” It appealed to his immigrant roots, as part of America’s treasured promise, she says.

Education worked that way for him, says Tsongas’s widow, U.S. Rep. Niki Tsongas, and he knew it could do the same for others.

“He understood the university had one of the most important roles to play in the city,” she says.

“Paul Tsongas’s vision for the university to help grow the city has been part of our blueprint for UMass Lowell’s future,” says Chancellor Jacqueline Moloney. “He was one of the first to see and encourage the power of urban partnerships. We’re proud to be associated with his name, house his papers and carry his legacy forward.”

Tsongas died Jan. 18, 1997 at the age of 55. Though cancer shortened his life, his legacy is writ large not only at the university, where he served as a trustee, but across Lowell, the city where he grew up and where he returned to raise his family.

Tsongas, who earned a bachelor’s degree from Dartmouth, a law degree from Yale University and a master’s from Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, served in the Peace Corps before returning to his hometown and immersing himself in civic life. Those days, the late 1960s, were dark ones for Lowell.

“If you didn’t get out, you were stuck in a declining mill city,” recalls Francis Talty, assistant dean of the College of Fine Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, who was a Tsongas campaign volunteer during his student days at UMass Lowell.

The mills that made Lowell a mighty industrial revolution power were long gone. Double-digit inflation raged. Businesses shuttered downtown.

“And here comes Paul Tsongas. He came back to Lowell and ran for city council,” says Talty.

“Lowell is a city where people are so deeply rooted, and it said so much about Paul as a person and what he believed. That was what you did—you went back to help your community. He believed he had an obligation to make a difference,” says Niki Tsongas, who was elected in 2007 to the same congressional seat her husband held three decades earlier.

Through hard work, sheer determination and an abiding love for his hometown, Tsongas helped change the trajectory of a dying mill city. Where some saw decay and despair he saw potential – and hope.

“It was his vision that led the way,” says Talty.

A pro-business Democrat, Tsongas pushed for partnerships between public and private entities to spur economic development. He filed the legislation that created the Lowell National Historical Park, an effort that united local, state and federal government with private industry and community groups. Tsongas firmly believed that the national historical park and Lowell, rich in history, could serve as a classroom for generations of students.

In 1991, the Tsongas Industrial History Center, a partnership between the Graduate School of Education and the National Historical Park that provides hands-on learning for students and educators, was named in his honor.

Also preserved on campus is the vast collection of Tsongas’s papers that are housed at the Center for Lowell History. Documents from his years as a U.S. representative and senator alone fill 720 boxes. The Center also holds his Boston, home office and presidential campaign papers.

“It really mattered to Paul that the university was connected to the community,” says Marty Meehan, former UMass Lowell chancellor, now president of the UMass system. “He didn’t want Lowell to be a place where people came but when the work day was done, got in their cars and drove away. And he didn’t want commuter students to do that. I learned from him. In my eight years as chancellor of UMass Lowell, I tried to make the connection between the university and the community even stronger.”

Tsongas, who served as a UMass Lowell trustee, served as a role model for many.

“Paul saw things before a lot of others in terms of what an urban community could be, as well as the role we could all play in making it work better,” says Meehan. “I always paid attention to anything he was fighting for. He liked to shake things up, and was not afraid of saying what needed to be said. He formed bonds with people you’d never expect him to, in the name of getting things done.”

Meehan made a point of reminding successive classes of students where the Tsongas Center – home ice for the River Hawks hockey team and the venue where UMass Lowell students receive their diplomas – got its name.

“When we took over the arena, there were rumors I would take Paul’s name off of it and sell naming rights for $5 million.” Meehan chuckles. “I never entertained that. Students come to this university, and I’m sorry they didn’t know about Paul already. So in the lobby of the Tsongas Center, there’s a tribute to Paul with four panels beneath his portrait, describing his life and times. You couldn’t describe it all there, but I felt that was really important to give to subsequent generations of students and Lowellians. I want them to know about the man whose name is on the building.”