Assoc. Prof. Jim Nehring Leads Workshops for Faculty

Image by Tory Wesnofske

Image by Tory Wesnofske

11/14/2018

By Katharine Webster

That standout professor who brings the curriculum to life? The one students remember throughout their careers because she taught them how to tackle a problem?

That doesn’t happen by accident. It takes hard work and a desire to learn effective teaching strategies, as well as how to analyze and improve those strategies. It also requires an understanding of psychology.

Yet at universities across the country, junior faculty are hired based on the quality of their research, not their classroom experience and teaching ability.

“We would never take a Ph.D. in biology, put her in a hospital and say to her, ‘Be a doctor.’ But we take that same person, put her in a university classroom and say, ‘Teach,’ even though most Ph.D. and postdoctoral programs don’t offer any training in teaching,” says Assoc. Prof. of Education Jim Nehring.

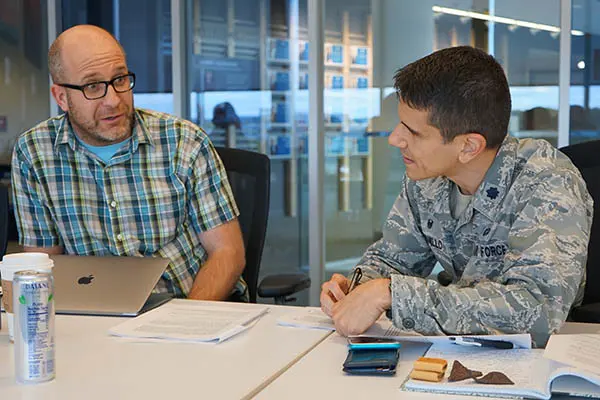

That’s where the College of Education comes in. Faculty can tap into the expertise of colleagues like Nehring, who specializes in professional development for educators.

Nehring says many professors become good teachers over time, but it’s often a process of trial and error, and there’s a great desire among faculty to learn how to do it better. So Vice Provost for Faculty Success Beth Mitchneck offered him a one-year fellowship to help faculty with course redesign.

Over the summer, Nehring coordinated and co-taught a series of workshops to help professors across the university ask and answer three questions about the holy trinity of course design – curriculum, instruction and assessment:

- What do I want students to be able to do?

- What experiences will I give them to ensure they learn how to do it?

- How will I know they can do it?

“The traditional method of teaching is for the professor to think about, ‘What am I going to say? How will I organize that?’” Nehring says. “We take a student-focused approach that involves solving problems and working with peers, coached by the instructor. It’s transformative.”

Faculty who participated in the workshops agree. A dozen are still meeting with Nehring, symposium-style, to discuss what’s working, what they need to refine and how to deal with new challenges.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

Sarah Rozelle is the proverbial biology Ph.D. who got thrown into the classroom – and then taught herself how to teach. As a grad student at Boston University, she attended a few teaching seminars for faculty. As a postdoc and adjunct professor, she took online courses on teaching through Coursera. She developed a passion for teaching that won her an appointment as assistant teaching professor in the Biology Department this fall.

Rozelle says she finds Nehring’s symposium “invigorating” because she gets to hear about strategies with which other professors are experimenting.

“It shows me that it’s OK to try something and fail in the classroom, and how to adapt,” she says. “Jim has shown me that just because I don’t do bench research anymore doesn’t mean that I don’t do research. Now I’m just doing research on how students learn.”

At a recent symposium meeting, Rozelle and the others shared some of their recent successes with strategies to promote active learning, a predictor of academic success. In large part, that means getting students to ask questions rather than sit passively in chairs.

Rozelle said she used to ask students if they had any questions – and got silence. Now, after she explains a concept or topic, she asks, “Are you comfortable with this material?” and asks students to give a quick thumbs-up or thumbs-down. If more than a few hesitate to give a thumbs-up, she tries explaining the material differently. She also asks, “What questions do you have about this part of it?”

“It’s partly about getting them to assume that they should have questions,” she said.

Jennifer Cadero-Gillette, assistant teaching professor in art history, said she tried out an exercise in helping students formulate good questions.

Image by Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico

Image by Museo Nacional de Antropologia, Mexico

Then she showed them the head in context, next to a human being, so they could see how enormous it was – and asked them to revisit their original questions. Their questions became much more sophisticated and they became genuinely curious about the sculpture carved by the Olmecs, an ancient civilization in what is now southeastern Mexico.

“They were so much more engaged for the rest of the class,” said Cadero-Gillette. “They were visibly having fun.”

David Willis, associate chairman for undergraduate studies in mechanical engineering, said breaking students into small groups for lab assignments and projects is standard. But invariably, students have approached him at the end of the semester to complain that another group member didn’t pull their weight, and that they didn’t want their own grade to suffer because of that.

So this year, Willis decided to tackle the dynamics of group work up front. He led a class discussion about best practices, including deciding on roles, setting up a schedule and handling a group member who underperforms. Students have found that empowering, he said.

“Students know intuitively that there are good and bad groups, but now you’re communicating that they can do something about that,” Willis said. “More students are identifying dysfunction and coming up and talking about it early in the semester, while there’s still time to address it.”