Training Tool Will Help Address Shortage of Behavioral Technicians

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

10/30/2017

By Katharine Webster

Nearly one in 50 children in the United States is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, usually before age 3, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But the number of people trained to help them isn’t keeping pace with the demand for services, in part because training takes place one-on-one with children with a wide range of symptoms, from the highest-functioning to those with multiple, severe issues.

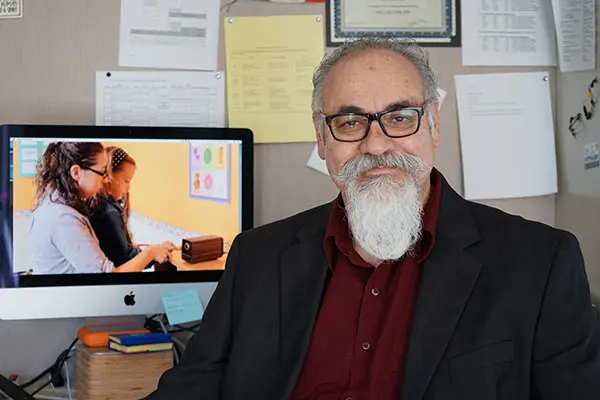

A professor in the Autism Studies Program may have just the right technology to help change that: immersive, interactive software to help professionals learn key treatment techniques.

Assoc. Prof. of Psychology Richard Serna has won a $250,000 grant from the National Institute of Mental Health to address the acute need for professionals trained in the most effective treatment for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) – behavioral intervention. Early treatment is critical in addressing intellectual delays and disabilities, as well as in heading off behavioral problems.

“Behavioral intervention is the most widely used and evidence-based treatment method for autism,” Serna says.

Serna is collaborating with Assoc. Prof. Charles Hamad, a UMass Medical School psychologist, to develop the new training tool. The software will feature a virtual child, programmed with learning difficulties associated with ASD, who can interact with people training in behavioral intervention techniques.

“The software will be useful in college classrooms, for new employees of agencies, special education teachers, paraprofessionals in the schools and even parents,” Serna says.

Serna is the principal investigator on the grant, which was awarded by the National Institute of Mental Health’s Small Business Technology Transfer Program. The program supports partnerships between university faculty and businesses for projects that involve translating academic research into useful products. Hamad, co-director of UMass Medical’s Center for University Excellence in Developmental Disabilities, also runs a software firm, Praxis Inc.

Serna, Hamad and Praxis have collaborated on previous NIMH-Small Business Technology Transfer Program grants to develop software for people with intellectual disabilities. The current award is a Phase One prototype grant, to develop and evaluate the interactive training software, Serna says.

Serna and Hamad will start with a virtual boy in a simulated environment, since boys are diagnosed with ASD at four or five times the rate of girls. The virtual boy will present common learning difficulties, and the software user will practice applying the best behavioral intervention technique to help the boy learn a new skill or desired behavior.

If the software user chooses the correct actions in the appropriate sequence – including praising the virtual boy each time he performs the desired skill or behavior, to reinforce his learning – the software will allow the user to move to the next lesson. If the software user does not implement the procedure correctly, the software will provide feedback until the user has mastered the technique.

“It’s of critical importance in behavioral intervention that you implement the procedures with accuracy and precision,” Serna says. “The software is like a flight simulator: It’s a do-no-harm way of practicing before you work with real children.”

Serna, who has previously created interactive video training software using live actors, says he got the idea for a virtual child in a realistic setting while watching his 17-year-old son play video games.

“I thought, ‘Why can’t we leverage that technology?’” he says. “With a simulation and a virtual child, we will have far more flexibility to change it and add features, and it will be less expensive than hiring actors and shooting and editing video.”

Once they have developed and evaluated a basic prototype, Serna and Hamad will seek Phase Two funding to develop it into a fully realized product.

“We’ll add voice control, more features, different virtual children, more languages, more interventions and more behaviors and levels of difficulty,” Serna says. “There’s a great need for such training in China, Brazil, Spanish-speaking Latin American countries and other places, so it could go worldwide.”