Criminologists and Psychologists to Study Personality and Messaging

12/12/2017

By Katharine Webster

Four social science professors have won a $794,000 Department of Defense Minerva Research Initiative grant to research the effects of extremist propaganda on different personality types, as well as the effects of different countermessaging strategies.

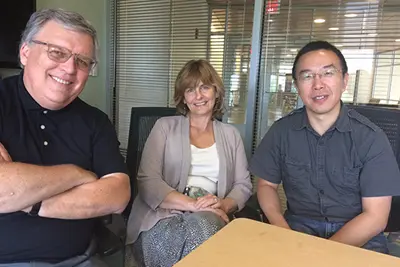

The three-year grant was awarded by the Office of Naval Research to three faculty members in the School of Criminology and Justice Studies – Asst. Prof. Neil Shortland, Prof. Arie Perliger and Asst. Prof. Jill Portnoy – and Psychology Prof. Thomas Gordon.

Shortland, the director of the university’s Center for Terrorism and Security Studies, is the principal investigator. A forensic psychologist by training, he says the grant will result in several studies that will answer basic questions about the effects of exposure to online extremist messages and countermessages, such as: What kind of messaging is most effective? What are the short- and medium-term results of exposure to extremist messages and countermessages? What personality characteristics in viewers make them more or less receptive to different kinds of messages?

The researchers will focus on psychological traits, including the subjects’ sensitivity to threats of punishment (behavioral inhibition) and rewards (behavioral activation), as well as their hostility, aggression and predisposition to extremist views.

“Millions of dollars are funneled into campaigns to counter extremism, but we have no idea what actually works,” Shortland says. “We need to start with models of human behavior that have already been validated, not with theories of radicalization. Old-school psychology has the kind of empirical value that doesn’t exist in this discipline at all yet.”

Ultimately, the researchers plan to produce a variety of reports and training materials for professionals engaged in understanding terrorist recruitment and creating countermessaging, a book and a series of podcasts for students, teachers, practitioners and the public.

The research will include a broad review of existing psychological studies on advertising and propaganda, personality, radicalization and video games. Fifteen to 20 undergraduates interning with the Center for Terrorism and Security Studies each semester will help collect and summarize the existing research. Master's and doctoral students will also be involved.

The professors will use that information to construct hypothetical models of how different personality types will react to different types of messages, and then will test their models on a representative sample of people in the main target group for terrorist recruitment: people age 18 to 26.

SparkNeuro, a private company that has extensive experience with political and commercial advertising, will use biomarkers including brain activity, heart rate, eye movement and tiny changes in facial expression to measure the subjects’ attention and engagement both before and during viewing. SparkNeuro will work with ForecastFwd, another private firm that develops algorithms based on such neurological and biometric data.

“The beauty of using neurological measures is you’re tapping into unconscious impulses,” Shortland says.

He expects the research results to be more complex and detailed than previous work in the field – and says some findings may prove counterintuitive. For example, past studies have shown that people with low or moderate levels of aggression who are exposed to extremist propaganda actually become more pro-social afterward.

“No one has done what we’re trying to do: predicting behavioral outcomes based on not just the type of propaganda, but also the type of person who is viewing it,” he says.