SEAAS Conference Brings Together Researchers, Policymakers, Artists and Activists

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

08/04/2017

By Katharine Webster

Asian-Americans are often held up as the “model minority.” Research shows that overall, they are happier and more successful than any other ethnic group.

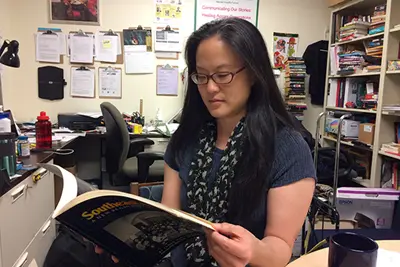

But that stereotype and those statistics belie the unique difficulties facing Southeast Asian-Americans who came to the United States as refugees of the Vietnam War or the Khmer Rouge’s reign of terror in Cambodia, according to Assoc. Prof. of Education Phitsamay Uy, who opened the Southeast Asian American Studies (SEAAS) Conference on campus last month.

“The issues faced by refugees and their children are different from those of fifth- or sixth-generation Chinese or Koreans,” said Uy, who studies high dropout rates among Southeast Asian-American youth.

Other issues include poverty, post-traumatic stress disorder, difficulty accessing health care, racism and language barriers, even between parents who struggle with English and children who speak nothing else, Uy and other speakers said.

Yet it’s difficult to advocate for or even study Southeast Asian-Americans because government data lumps them all together with immigrants from India, China, Taiwan and Korea, said Katrina Dizon Mariategue, immigration policy manager for the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center in Washington, D.C., founded in 1979 to aid refugees of the Vietnam War.

“Before we can even talk about doing research, just getting good data is a struggle,” she said.

UMass Lowell faculty are engaged in numerous research projects with the Southeast Asian-American community on topics ranging from health care and immigration to education. Most recently, faculty members won a large grant to create a digital archive of Southeast Asian history in Lowell, where more than 20 percent of the population is of Asian ethnicity, according to the U.S. Census. The city also boasts the second-largest Cambodian community in the country.

At the conference, a breakout session on community organizing was led by family members and supporters of the “Minnesota 8” – eight Cambodian-Americans who came to the U.S. as babies or small children but were detained by the government’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) department for deportation last summer because of crimes, ranging from property damage to assault, that they committed years ago.

Although most were born in Thai refugee camps, five of the eight have been “repatriated” to Cambodia, a country they’ve never known or don’t remember, where they have no relatives and where they don’t speak the language. Two are still in detention, awaiting immigration hearings, and one, Ched Nin, was freed in February after an immigration judge found that his deportation would cause undue hardship to his wife, Jenny Srey, and their five children.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

“A lot of people, like the politicians who make these decisions, aren’t aware that families are being separated like this,” Nin said.

Dizon Mariategue, who is helping the Minnesota 8, said Southeast Asian-Americans – whose parents were often so traumatized by war or hindered by lack of education that they failed to obtain U.S. citizenship for themselves and their children – are disproportionately affected by such deportations.

“It’s a huge human rights issue,” she said. “We also believe it’s triple jeopardy: They’ve served prison time for their crimes, then they’re re-imprisoned by ICE, and then they’re deported.”

The conference also celebrated Southeast Asian culture with a film festival, writing and blogging workshops, poetry readings, dance and theater – including the Lowell-based Angkor Dance Troupe and Flying Orb Productions.

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

“I started off breaking, so she thought I looked like a boy, and she said, ‘Be a girl,’” Hoang said. “So I did the Vietnamese pageant and modeling circuit and she said, ‘Not that kind of a girl.’ It was very confusing.”

“The only time the family likes her dancing is in the Catholic Church,” added her sister, Uyen Hoang, a graduate student in Asian American Studies and Community Health Sciences at UCLA who read a paper on the potential of vogueing to liberate young Vietnamese-American women from nationalistic feminine stereotypes.

Loan Hoang has gone to Vietnam to teach breaking and other contemporary dance styles. She taught a vogueing lesson in the workshop, too – and everybody danced.