Anthony Szczesiul Says New Book Was Inspired by Students

Image by K. Webster

Image by K. Webster

09/27/2017

By Katharine Webster

When English Prof. Anthony Szczesiul taught his first class on Southern literature at UMass Lowell in 2003, he asked his mostly Massachusetts-raised students to jot down a list of things they associated with the South and Southern literature.

“The only thing on every student’s list was ‘Southern hospitality,’ even though they couldn’t really explain what it meant,” he says. “They also listed things like slavery, segregation and racism. We talked about how you reconcile those competing views of the South.”

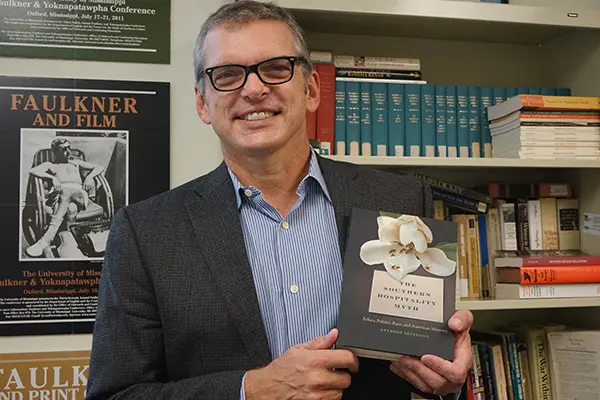

Out of that exercise grew the idea for Szczesiul’s new book: “The Southern Hospitality Myth: Ethics, Politics, Race and American Memory,” published in June by the University of Georgia Press as part of its New Southern Studies series.

Szczesiul, who grew up in and around Detroit, earned his Ph.D. in American literature at the University of South Carolina. His first book was “Racial Politics and Robert Penn Warren’s Poetry.”

Q: How did the idea of Southern hospitality get started?

A: Historians trace it to the social customs of wealthy planters in different Southern colonies during the 1600s and 1700s. But no one used the phrase “Southern hospitality” until the 1820s or 1830s, when national debates about slavery intensified. As white Southerners felt themselves to be under attack, the idea of “Southern hospitality” became a way of defending their lifestyle and a political system that depended on slavery.

For most of its history, this myth about Southern hospitality created a sense of solidarity and belonging among white Americans in all parts of the country, while relegating African-Americans to service roles, first as slaves and later as domestic workers.

Q: The North is often portrayed as cold and inhospitable compared to the South. Is it?

A: In the 19th century, hospitality was an important social ritual everywhere. In the book, I talk about a Virginian who praises Yankee hospitality as being more authentic because it doesn’t rely on slave labor. Also, many Northern progressives and abolitionists defined hospitality differently, based on what they saw as the Biblical command to be open to differences and welcome the stranger, including runaway slaves. It’s easy to welcome people who are just like you. They believed that true hospitality is hard, because it involves risk.

Today, we rarely think of this ethical ideal of hospitality, but people can and do act upon it. A recent example is the victims of the mass shooting at Mother Emanuel church in Charleston, S.C., in 2015. Some of them were older African-Americans who had grown up under segregation and would have had good reason to be suspicious of an unknown white man showing up unannounced at a black church. But they were willing to look beyond the traumas of the past, open themselves to risk and welcome a stranger. It cost them their lives.

This true ethic of hospitality has never been part of the Southern hospitality myth, although there are glimpses of change.

Q: Your book seems especially timely now, given the debate over Confederate monuments and Southern history. You also talk about the anti-immigrant movement.

A: It harks back to that idea of true hospitality. After Alabama passed a law in 2011 making it a crime to help illegal immigrants – a kind of modern-day version of the Fugitive Slave Act – a lot of Southern churches, social justice organizations and others opposed it. They argued that Southern hospitality requires Southerners to welcome immigrants, the strangers in our midst.

Q: Is there a distinctly Southern culture, or not?

A: Our idea of the South is largely imaginary, but it has real effects and consequences. We project both negative and positive things onto the region. The nation has projected its failures in matters of race onto the South so that the rest of us could say, “That doesn’t happen here.” We’ve also projected positive images of community, tradition, manners and hospitality.

But this monolithic idea of “The South” is fading. The South today is incredibly diverse. It’s rural and urban, and it’s as politically and economically divided as the rest of the country.

Q: Then why do we still talk about Southern hospitality?

A: Because the myth of Southern hospitality serves the rest of the nation as much as Southerners. After the Civil War and during Jim Crow segregation, it helped white Northerners accept reconciliation with the South. Through most of the 20th century and continuing today, it has been a vehicle for economic development through travel and tourism, peddling Southern food and a romantic vision of a more leisurely, rural lifestyle.

Q: The popularity of Southern Living magazine and the national obsession with Southern barbecue come to mind.

A: We often talk about pop culture in my classes, and students gave me some great examples for the book. A couple of years ago, I taught an honors seminar on the Southern plantation. We read plantation manuals, slave journals, pro- and anti-slavery novels and films. We also looked at some of the commercial aspects of Southern hospitality today -- the big market for plantation weddings, for example. On some websites advertising authentic plantation weddings, we found photographs of white bridesmaids hanging out of old slave cabin windows. That was an eye-opener for all of us.